Ostara is present all around me. She is in the sky above me and is in the cool rain shower. She is the light that warms the earth below me, receptive and fertile. She is in the birdsong of newborn chicks. She is in the tiny buds of leaf and flower, intoxicating me with their scent.

Family traditions are celebrations or activities that are passed down between generations. But have you ever wondered why we celebrate Easter with colored eggs, chocolates, and bunnies?

The ritual Easter basket and the egg hunt of my childhood were a tradition in our home, one that I looked forward to every spring. In the afternoon, we came together as an extended family with my Grandparents to enjoy Easter dinner. This was a custom I also passed down to my children when they were small and later with my grandchildren.

But did you know that many of us preparing to celebrate Easter may not realize where this holiday originated? Maybe the festival’s name helps us understand the pagan roots we have come to love.

The Hidden Pervasiveness of the Sacred Feminine

Several years ago, I facilitated a webinar on The Alchemy of Renewal and Regeneration for Sensually Excitable Women. While doing some research, I discovered the Earth-maiden goddess Ostara and why Easter here in the West became associated with her traditions.

During the Paleolithic and Neolithic, there is ample evidence of widespread reverence for the female form. Many of the forms found are beautifully well-nourished suggesting fertility. The Goddess was appreciated as a “creator, law-maker of the universe, prophetess, provider of human destinies, inventor, healer, hunter and valiant leader in battle.” The sacred feminine appeared in all aspects of our ancestors’ daily life.

During the Paleolithic and Neolithic, there is ample evidence of widespread reverence for the female form. Many of the forms found are beautifully well-nourished suggesting fertility. The Goddess was appreciated as a “creator, law-maker of the universe, prophetess, provider of human destinies, inventor, healer, hunter and valiant leader in battle.” The sacred feminine appeared in all aspects of our ancestors’ daily life.

Later in 14th BCE, the belief in a universal deity emerged. The monotheistic religions introduced an exclusively male order: God, King, Priest, and Father. As the major world religions evolved over thousands of years, the reverence for the feminine began to retreat from view.

Pagan Beliefs of the Modern Era

Strange as it may seem, Easter traditions are a relic of pagan days. Today, instead of a history of the ancient goddess celebrated for thousands of years, many are most familiar with the dominant creation story of Adam and Eve and later the birth and resurrection of Jesus.

In the Western tradition, this ‘belief in one god’ refers explicitly to the monotheistic God of the Bible, the God of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

As Christianity spread through the northern regions of the world to help with conversion, they often integrated the pagan customs as means of compromise. Most major holidays we now celebrate today have some connection to the changing of seasons that ancient people celebrated. The festivities centered around the winter and summer solstices.

The festival of Ostara was integrated into western culture soon after Christianity began spreading through the northern hemisphere. Even as she retreated deeper into the recesses of our collective psyches, her presence was a source of celebration.

Ostara who?

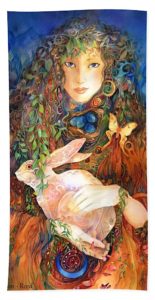

Ostara is the Goddess of Spring. She characterizes the awakening Earth, the first warm breeze, blossoming flowers, bird songs, nests, eggs, and hares. She beckons the animals to venture out from their winter shelters, encourages buds to sprout and flower, and emits a life force throughout the land.

Ostara was usually depicted as a maiden adorned with flowers and fresh greens. She was old enough to bear children but was not yet a mother. She often dances and is joyous, but can just as easily turn solemn, like the sunny spring weather suddenly turning rainy and grey. Like spring, she is capricious, innocent, and knowing in turn.

Ostara was usually depicted as a maiden adorned with flowers and fresh greens. She was old enough to bear children but was not yet a mother. She often dances and is joyous, but can just as easily turn solemn, like the sunny spring weather suddenly turning rainy and grey. Like spring, she is capricious, innocent, and knowing in turn.

Full of potential, she represents the blossoming of inspiration and creativity that brings new life, the beginning of new ideas or projects. She embodies the opportunity for growth and rebirth after winter in our own psyche, awakening passion, and aliveness.

Celebrated initially during the spring equinox (read Spring Alchemy Meditation), Ostara was known as the source of the radiant dawn of new light. The Equinox had a positive outlook for people and adapted easily for the Christian resurrection.

Oestre, Eostre, Easter

By way of linguistics, Easter gets its name from the pre-Germanic goddess of spring, Oestre or Eostre. The origins of her name can even be traced back to the ancient Assyrian goddess Ishtar, and the Sumerian goddess, Inanna.

Eostre is related to Eos, the Greek goddess of dawn; both can be traced back thousands of years ago as the representative of the sacred feminine. The word east, the direction of the rising sun, originates from Germanic and Austro-Hungarian words that share the word root with aurora. The root meanings of all words convey, “to shine.”

Interestingly, Eostre also applies to the word estrogen, which is essential to women’s fertility.

It is from Eostre that the Christian celebration of Easter has evolved. As it happened, the pagan festival of Eostre occurred at the same time of year as the Christian observance of the Resurrection of Christ. It didn’t take the Christian missionaries long to convert the Anglo-Saxons when they encountered them in the 2nd century.

And even though Christians had begun affirming the Christian meaning of the celebration, only the German-English speaking countries refer to the festival as Easter.

Contemporary pagans (non-Christians) have generally accepted the spelling Ostara (Oh-star-ah), which honors the goddess of fertility, rebirth, and renewal.

Most Europe refers to “Easter” using a range of words derived from the Hebrew for Passover, “Pesach.” In Italy, Easter is known as Pascha; in Spain, Pascua; Pasques in France and Pasti in Romanian.

April is Eosturmonath

The naming of the celebration as “Easter” seems to be associated with the fourth month of the year. April, in old English, is called Eosturmonath — Eostre’s month, which is when Easter is celebrated.

The date of the Christian Easter is determined by the phase of the moon about seven days after the astronomical full moon. Easter always falls on a Sunday between the equinox in March and April 22.

Hares and Eggs

The Easter Bunny has a long and deeply rooted history in the Christian holiday that has its roots in pagan traditions.

Over the centuries, Ostara’s two symbols represented the primal force of fertility: the cosmic egg and the mad march hare, which began to multiply with ferocious frequency in the spring. The hare, a slightly larger rabbit considered a rodent, has become the Easter Bunny, who brings eggs to children on Easter morning.

Our Anglo-Saxon ancestors celebrated the arrival of spring with feasts and games. It seems hare-hunting was a common Easter activity in England.

Our Anglo-Saxon ancestors celebrated the arrival of spring with feasts and games. It seems hare-hunting was a common Easter activity in England.

The tradition of an egg-laying hare named “Osterhase” or “Oschter Haws” was first introduced in the 1700s by German immigrants to Pennsylvania who brought the legend of the egg-laying hare.

The legend says that the hare was originally a bird who died and was changed into a hare by Ostara. On her festal day, the hare exercises its original bird function to lay eggs for the goddess in gratitude to her.

The hare would lay colorful eggs as gifts to children who were “good.” Children would make nests where the bunny could leave her eggs and sometimes set out carrots if she was hungry.

Over time, the Easter bunny’s delivery expanded from just eggs to including other treats such as chocolate and toys. Eventually, the custom became a widespread commercial Easter tradition that brings in big money each April. The first chocolate eggs appeared in France and Germany in the 19th Century. As chocolate-making techniques improved, hollow eggs like the ones we have today were developed.

On Easter Sunday in Anglo-Saxon countries like the UK or USA, it’s customary to have an Easter Egg Hunt with children looking for hidden brightly colored eggs. Today, families hide chocolate, painted or plastic eggs filled with treats in their garden or house. The children, who think the eggs come from the Easter Bunny, try to find them.

Decorated Eggs

Decorated eggs were associated with pagan festivals celebrating spring. This practice predates Christianity by approximately 1000 years.

From ancient history to the present, eggs have been an important symbol in many cultures. They are part of the creation myths of many peoples, the “cosmic egg” from which all or parts of the universe arise—eggs symbolizing life, renewal, and rebirth, figure in much of human folklore.

As an aside, did you know that chickens raised in natural lighting quit laying eggs when the days are short in winter and begin laying again as the days lengthen? March and April are their peak time of year, and those eggs were a valued and welcome protein source for our winter-hungry ancestors.

In several cultures, eggs in the spring were gathered and used to create talismans and ritually eaten. The gathering of different colored eggs from the nests of various spring birds may have given rise to two traditions still observed today – the coloring of eggs in imitation of the various pastel colors of wild birds and the Easter egg hunt.

Colored eggs appear on the altars made for the new year known as Nowruz, celebrated at the vernal equinox. This tradition has ancient roots in Persia and Zoroastrianism but is now practiced across Eurasia by Persian and Turkic peoples of various faiths.

In Jewish tradition, a pure white roasted egg is part of the seder plate at Passover. Orthodox Christians in Mesopotamia took the symbol of the Passover egg and dyed it red as a symbol of Christ’s blood.

The custom may date back to the 13th century when eggs were traditionally considered a forbidden food during the Lent season. Decorating eggs as the fasting period ended, eating them an even more celebratory way to feast on Easter Sunday.

The custom may date back to the 13th century when eggs were traditionally considered a forbidden food during the Lent season. Decorating eggs as the fasting period ended, eating them an even more celebratory way to feast on Easter Sunday.

The Anglo-Saxons painted eggs with their hopes and dreams and presented them as a gift to Ostara in the spring. Mothers would bury a raw egg in the earth by the entrance to the home in hopes the goddess would help her children realize their dreams for the year.

The tradition in Ukraine to paint eggs, also known as pysanky, comes from the Ukrainian word “to write,” which goes back more than 2000 years. The beautifully decorated Easter egg tradition preserves some of the cultural symbolism and power that was once very common across Eurasia and is still found in some places today.

As the tradition of dyeing eggs expanded beyond the Pennsylvania German culture, commercial dyes and pre-dyed eggs appeared by the late 1800s.

Ostara’s Legacy

Ostara’s legacy lives on through her presence in the traditions we celebrate with our children and families each spring. Now that you know where the Easter tradition came from, perhaps you will share this little bit of history with your own families.

Mindful of Ostara’s presence during the springtime brings on sensory aliveness! All spring flowers, particularly daffodils, primroses, violets, crocuses, buttercups, catkins, pussy willows, and colors that are bright greens, yellows, and purples, are associated with Ostara.

It doesn’t require articles of faith or complex beliefs to embrace a living relationship with the goddess of spring. Honoring our collective sacred relationship with nature and life and sharing gratitude for her blessings with our loved ones allows us all to celebrate timeless renewal during Easter.

Remember Ostara’s legacy as you carry forth the seasonal traditions with your family, the joy of spending time together is where we feel her blessings most.

Happy Easter!

All my aromatic love,

Vidya